Casey Handmer 22 July 2022 (original post)

The team at Terraform Industries is now 11 people working towards a near term future where atmospheric CO2, much of it centuries of unpriced industrial waste, becomes the preferred default source of industrial carbon. Our family of technologies will displace drilling and mining as sources of carbon and, in the process, stop the net flux of carbon from the crust into the atmosphere and oceans that is causing anthropogenic climate change.

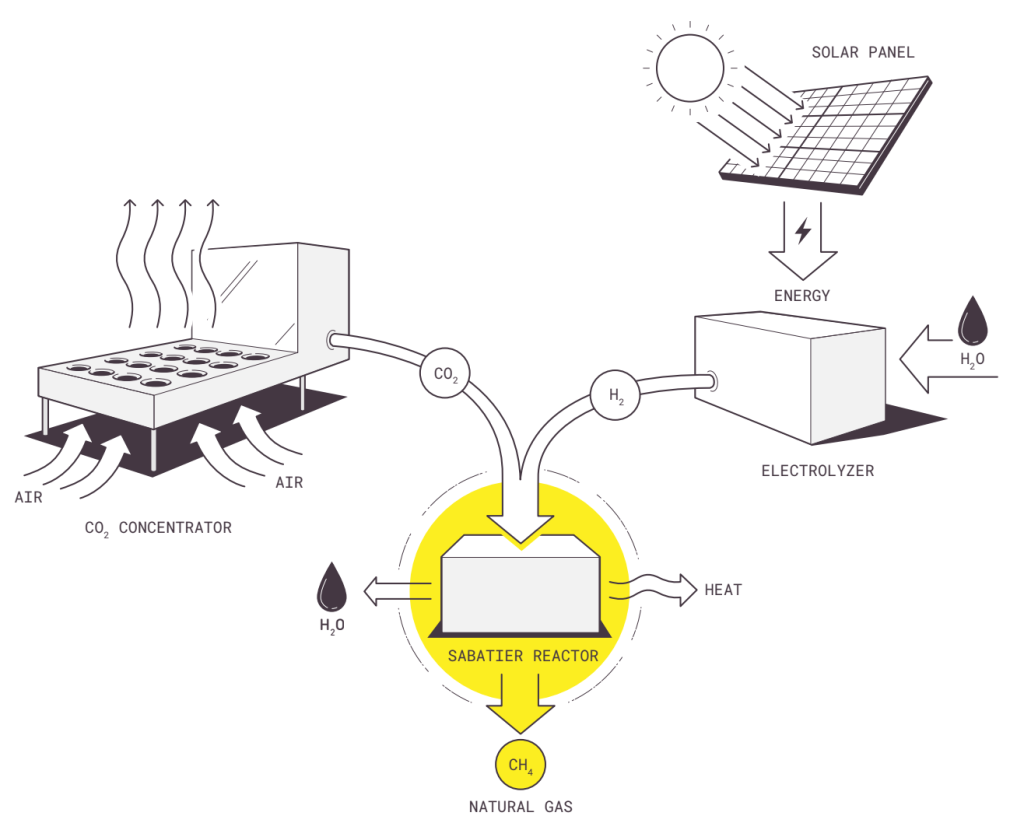

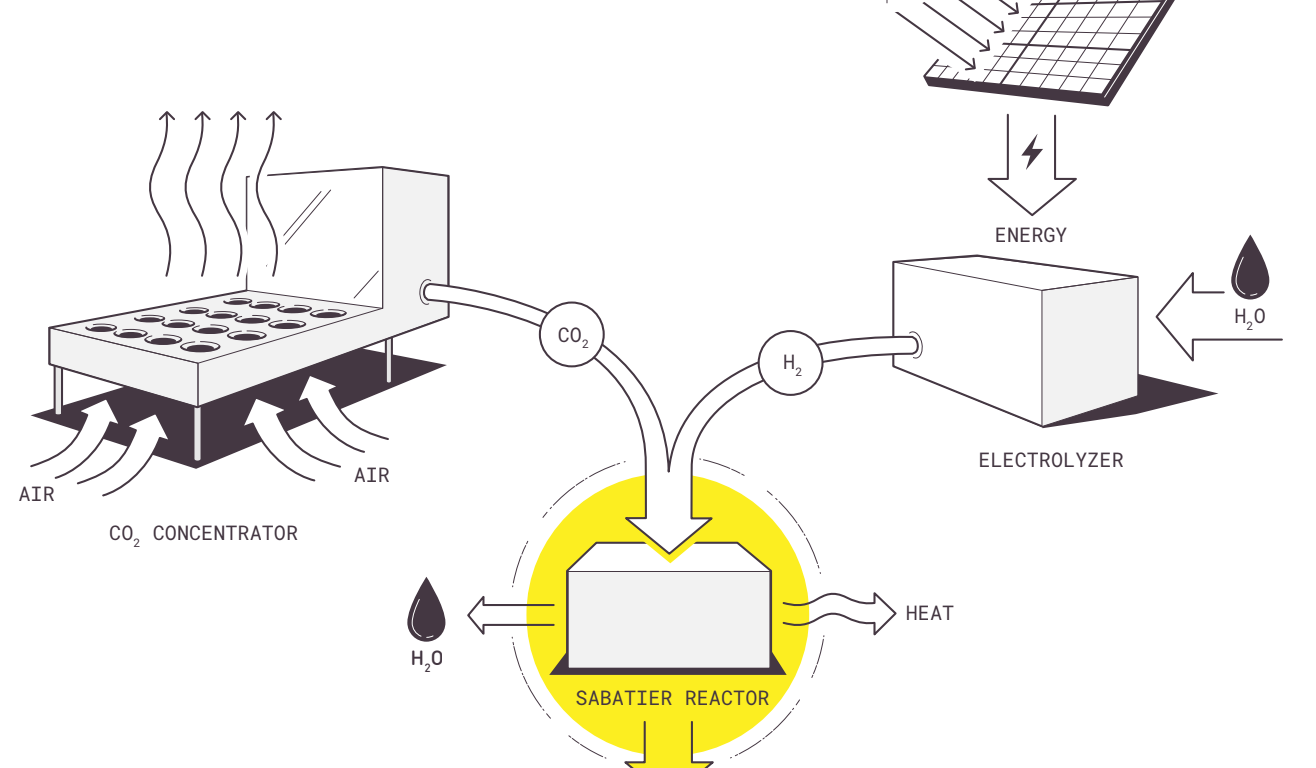

Our process works by using solar power to split water into hydrogen and oxygen, concentrating CO2 from the atmosphere, then combining CO2 and hydrogen to form natural gas. Very similar processes can produce other hydrocarbon fractions, including liquid fuels. Synthetic hydrocarbons are drop in replacements for existing oil and gas wells and are distributed through existing pipeline infrastructure. As far as any of the market participants are concerned, fuel synthesis plants are less polluting, cheaper gas wells that convert capital investment into steady flows of fuel in a boringly predictable way.

Most recently, Terraform Industries succeeded in producing methane from hydrogen and CO2.

There is nothing particularly special about the technological approach we’re taking. Each of the various parts is built on at least 100 years of industrial development, but up until this point no-one has considered scaling these up as a fundamental source of hydrocarbons, because doing so would be cost prohibitive. Why? The machinery is not particularly complex, but the energy demands are astronomical. Yet as our atmospheric CO2 concentration creeps steadily ever upwards year over year, our ability to extract silicon from rocks and transform it in frankly magical ways continues to progress.

One of these ways has produced the cheapest electricity ever. Electricity so cheap that in an ever growing number of markets it now makes more sense to turn solar electricity into hydrocarbons, than to burn hydrocarbons to make electricity.

To a good approximation, the Earth is a pile of iron atoms (the core) surmounted by a pile of oxygen atoms (the mantle and crust), with other, smaller atoms filling in the gaps. One of the most common of these is silicon, and the silicate minerals are the major component of 95% of rocks. To say that extracting sufficiently pure crystalline silicon is difficult is an understatement, but we’ve been able to do it for longer than a human lifetime and we are continuing to make steady progress. The silicon industry turns over nearly a trillion dollars a year, so the profit motive is doing its job!

Silicon is one of several materials that can be used to make solar photovoltaic (PV) panels, in addition to its starring role in integrated semiconductors inside computers. The solar panel industry has been growing by about 25-35% per year for the last decade, making steady progress on cost and becoming a mainstream energy source to the point where its continued displacement of other grid power sources is partly limited only by the battery manufacturing ramp rate, itself redlining at about 250%/year!

Wright’s Law describes the tendency of some products to get cheaper with a growing manufacturing rate. It is not guaranteed by the laws of physics, but rather describes the outcome of a positive feedback loop, where a lower cost increases demand, increases revenue, increases investment, increases cognitive effort, and further lowers cost. For solar technology, the same effect is known as Swanson’s Law, and works out at 20% cost reduction per doubling of cumulative installations since 1976.

This is not the full story, though. Solar has only been cost competitive with other forms of grid electricity generation since about 2011, at which point investment and engineering effort greatly increased. Since 2011 there has been an acceleration of production growth rate and an increase in the learning rate, such that the cost decline is now 30-40% per doubling. For more details, check out Ramez Naam’s excellent blog on the topic.

For more than a decade, some industry experts have predicted that cost improvements, and installed capacity, will imminently flat line. The chart below shows the “hairy back” of these failed predictions.

https://rameznaam.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/IEA-Solar-Growth-Forecasts-vs-Reality-Simon-Evans-Carbon-Brief.jpg

It has been clear to me that absent a fundamental physical limit being reached, there is no reason to suspect that the still accelerating positive feedback loop would slow down or stop. Here’s a post I wrote about the topic back in 2018. If anything, we should expect production growth rate to increase from around three years per doubling to perhaps two years. It is still not fast enough.

Global solar production last year (2021) was about 190 GW. With 30% cost reduction per doubling, solar continues its steady march into adjacent competitive energy markets and its displacement and augmentation of energy generation.

What people have missed is that reaching cost parity on fuel synthesis will unlock huge new demand centers and flatten the gradient on the demand curve enough. Even if we copied each new factory 5 times, reducing learning rate by 5x in exchange for increasing production 5x, price declines will still stimulate far more demand than this expanded production can meet.

Regular readers of this and similar blogs will be familiar with this chart of global photovoltaic power potential. Some places will win the solar power lottery, much as other places have historically “won” the oil lottery. Unlike oil, solar resources are much more evenly spread over the world. On the chart above, the US south west receives around 5.2 kWh/kWp, while notoriously dreary England receives only 3.2 kWh/kWp. Does this mean that Britain should import solar power from north Africa? Not quite.

At 30% cost reduction and three years per doubling of production rate, Britain’s cost will match Los Angeles’ in less than six years. There are a few parts of the world, particularly at extreme northern latitudes, where solar power is truly painful, but they are few and their population is low, compared to the billions who live in generally sunny-enough locations. When their local cost of solar falls to the point where synthetic atmospheric CO2-derived hydrocarbons are cheaper than importing it from (probably) the Middle East, demand will increase substantially. How much?

The chart below is a basic Sankey diagram showing energy flows in the US in 2021. A much more thorough (though less screenshotable) version can be found at Energy Literacy. The Quad is a unit of energy:

A quad is a unit of energy equal to 1015 (a short-scale quadrillion) BTU,or 1.055×1018 joule (1.055 exajoules or EJ) in SI units.

The unit is used by the U.S. Department of Energy in discussing world and national energy budgets. The global primary energy production in 2004 was 446 quad, equivalent to 471 EJ.

Some common types of an energy carrier approximately equal to 1 quad are:8,007,000,000 gallons (US) of gasoline

293,071,000,000 kWh

293.07 terawatt-hours (TWh)

33.434 gigawatt-years (GWy)

36,000,000 tonnes of coal

970,434,000,000 cubic feet of natural gas

5,996,000,000 UK gallons of diesel oil

25,200,000 tonnes of oil

252,000,000 tonnes of TNT or five times the energy of the Tsar Bomba nuclear test

12.69 tonnes of uranium-235 (with 83.14 TJ/kg)

6 s sunlight reaching Earth [10 hours a year for 8 billion people to enjoy US standards of living]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quad_(unit)

In particular, the US consumes about 37 Quads of energy for electricity generation, of which about a third goes into wires and the rest is lost in thermodynamic heat loss in generating stations and transmission. Ceteris paribus while solar PV and batteries are much less inefficient, PV capacity factors are limited by daytime sunlight, seasonal daylight variations, poor weather, and mismatches between times of peak generation and consumption. The end state of the solar electricity build out will likely see 3-6x overbuild in nameplate capacity, and large variations in electricity price by time of year, day, and location. These price differences, incidentally, already drive the engine of arbitrage which has turbocharged the battery industry.

Analysts recognize that coal and natural gas used for electricity production will eventually be displaced by renewable generation. Just as converting chemical energy in the form of fuel into electricity endures 45-75% thermodynamic losses, converting electricity back into chemical fuels loses 60-70% of the energy in the process. Converting solar power into natural gas only to burn it in a gas turbine power plant could help with long term seasonal energy storage but is so much less cost competitive than other ways to stabilize electricity supply that we should expect this usage modality in, at most, niche cases.

But what of other uses of carbon-based fuels? In the US, roughly twice as much energy is consumed by transportation, industry, and other uses, as in direct electrical generation. Electrification of cars and trucks proceeds apace but other, more fuel hungry forms of transport including aviation are harder to convert. Fuel uses for high temperature industry will continue to demand non-electrical processes. In particular, it’s easy for industry to transition to purely electrical energy if it’s cheaper for them to use it, but not if it’s not.

If we want to use organic market demand for cheap hydrocarbons to fund the build out of a global network of solar powered atmospheric CO2 scrubbers that can remove a meaningful fraction of our planet-warming legacy industrial CO2 waste, then we have to compete on price and convenience, not just on warm-and-fuzzies.

Unlike the electrical grid where, by default, power is generated and consumed simultaneously, capacity factor and intermittency are less of a concern for synthetic hydrocarbons, since existing infrastructure and use cases already enable days, if not weeks, of storage. The power intensive parts of fuel synthesis plants, most prominently electrolyzers, should only operate during the day. The impact of diurnal power supply variations on plant design demands only lower capital costs so that amortization is less painful. Since rapid scaling requires low capital costs anyway, and capital costs usually buy energy efficiency that we neither need, nor want, this trade is not particularly painful.

Synthetic fuels’ displacement of existing sources of coal, oil, and gas will require only enough overbuild to compensate for daytime operation, thermodynamic losses, and any additional induced demand. Terraform’s megawatt scale plant design targets 30% efficiency, but will probably gradually trade that for lower cost over time as power costs continue to fall.

13 Quads of electrical consumption in the US will require perhaps 50 Quads of solar generation, profitable deployment of batteries, and no further miracles as displacement occurs organically over the next 10-20 years. 70 Quads of fossil fuel consumption will be displaced by about 240 Quads of solar generation, and there will be a steep price incentive to enable this displacement.

In the US, we are anticipating a 6-10x demand increase once solar costs cross the critical threshold. In the current market, production capacity increases lag market expansion caused by cost reductions, but only slightly. In fact, in an era of steady displacement, learning rate is pegged to these market characteristics since it reflects a roughly optimal R&D investment strategy. Once we cross the synthetic fuels market expansion threshold, the legacy learning rate glide slope will be wildly inadequate to serve expansions in demand.

What is the solar cost threshold of interest? One barrel of oil contains about 1.7 MWh of chemical energy. Synthesizing a barrel of oil requires about 5.7 MWh of electricity at 30% conversion efficiency. Crude oil prices are between $60 and $100/barrel, indicating cost parity at between $10 and $17/MWh. There are already solar farms installed in some places that sell power at these prices, and between now and 2030 solar costs should come down at least another 60%.

Let’s look at how small price reductions will affect demand in more detail. I sampled these two datasets for world solar PV potential and population density at millions of locations, then marginalized over population and binned by price decreases of 1% per month. 1% per month corresponds to 25% price reduction and 3 years per doubling of production, which is slightly conservative.

The curve above shows how much synthetic fuel demand will occur as a function of time, assuming only 1% solar price reduction per month, 30% fuel synthesis efficiency, and cost parity at $10/kcf of natural gas or $60/barrel of crude. The shape is a function only of the distribution of sun that humans enjoy wherever they live. Tweaking efficiency, price drop rate, or cost parity price only changes the timeline scale, and not by more than a few years each way. Within 8 years of first hitting price parity anywhere, more than half of the world’s population will be within the addressable market, requiring >100 TW of solar PV generation.

This is what I mean when I say we’re looking at a very near term demand unlock, and that we’re going to need a lot of solar panels. On one hand, contemplating scaling the PV industry to meet this demand is a daunting prospect. On the other, here is a market and technology based mechanism that can organically displace fossil carbon use in a single generation and leave behind enough CO2 capture machinery that we can choose to draw down 100 ppm of CO2 with a tiny tax, rather than the hypothetical reorganization of the entire world economy and re-instantiation of feudal levels of poverty and hunger for most of the world’s populace.

Earlier this year we were anticipating hitting cost parity in our beachhead markets some time this decade. Then Russia invaded Ukraine, and European energy security evaporated. Things would look a bit different, perhaps, if the existing European nuclear power industry hadn’t been shot in the foot. If European solar manufacturing had maintained its momentum. If the wind turbine industry was treated as seriously as Airbus’ aircraft manufacturing. These are hypotheticals, and we cannot change the past. What we can change is how we adapt in future.

No matter what happens, Europe is looking at a cold winter. We absolutely should do everything we can to reduce conflict, improve building insulation and resiliency, and safeguard existing energy supply chains. This is necessary but it is not enough. We also need to choose a future of abundance, and that means an immediate emergency crash program to mass produce solar panels wherever and however we can at the highest possible rate. We no longer have the luxury of a decade to quibble about site placement or minor environmental impacts. The alternative is catastrophic climate change and mass starvation. The impact of solar farms on unimproved land is low, and trivial to reverse if, in future, we decide to remediate land. Certainly, it is far less impactful than agriculture, which already consumes a much higher fraction of the Earth’s land surface than solar panels ever will.

Terraform Industries’ synthetic natural gas process is not particularly complicated or difficult to achieve. We intended to make it easy to scale and deploy. If Europe had enough solar power deployed, even at current European solar prices, we could synthesize desperately needed natural gas at lower cost than transoceanic liquefied natural gas (LNG) importation, which is the next best option.

At current prices, Europe spends nearly a billion dollars per day on natural gas imports. Solar panel factory construction is cheap by comparison, even at the required scale. Europe would need about 1.5 TW of solar power generation to displace all imports, though even 10% of this would be very helpful. That’s about 0.3% of Europe’s land area. At current prices, completing this build out would cost about the same as a year of natural gas imports, and the end result would be persistent European energy independence for the first time in its history.

If you are a European policy maker, entrepreneur, investor, or manufacturer interested in learning more, please reach out. Terraform has no immediate plans to enter the European market but we will help anyone we can get this process underway.

The Russia-Ukraine conflict has accelerated the cost threshold transition. What previously might have occurred in 2026 occurred on February 24, 2022. Beyond that point, provided that the learning rate doesn’t fall below 5% (it is currently 30% and increasing), additional production will lower prices and expand market demand faster than it can sate it, more or less indefinitely. Already, new solar installations in Europe (cloudy, rainy Europe) will pay for themselves in less than three years. This is faster than nearly any energy infrastructure in history.

At current rates of production growth, the supply/demand mismatch will see a 10 year backlog between the time when local solar powered synthetic fuel production reaches cost parity with fossil sources, and when solar supply will be available to meet that demand. Ten years! Ten years of energy insecurity. Ten years of a Russian dictator unilaterally setting foreign policy anywhere its pipelines reach. 500 GT of additional, avoidable CO2 emissions. Perhaps 0.9°C of avoidable temperature rise. Hundreds of millions of lives harmed or prematurely ended by climate change.

We’re going to need a lot of solar panels. If 300 Quads are adequate to meet current US needs, then roughly 3000 Quads are needed to saturate global demand at US standards of living. Yes, solar synthetic fuels can overcome oil scarcity even in traditionally underdeveloped places. I expect that usage patterns, efficiency targets, and consumption will shift quite a bit by the time we complete this task, but we have to baseline somewhere. 3000 Quads is roughly 300 TW of solar generation capacity, occupying about 5% of Earth’s land surface area, and split between roof top installations in cities and dedicated plants on nearby less developed land. For comparison, agriculture uses 18% of Earth’s land surface area, and largely uninhabited deserts are 33%. Ultra low cost solar power will be ground mounted, and ideally rolled off a spool onto the ground similar to chemical-free plasticulture today. Synthetic fuel byproducts include oxygen and water, so limited direct irrigation in arid fuel production areas will also be possible.

300 TW is a lot of power. Roughly 20x our current global electrical production capacity. At that scale, hydrocarbon fuels will be cheaper than they are today nearly everywhere, while electrical power will be up to 20x cheaper, strongly favoring direct electrification where possible. Cheaper fuel means less scarcity, less poverty, and less damage to the environment.

Current global PV production is about 200 GW/year, with production doubling every three years. At this rate we’ll get to 300 TW cumulative production in 2048 or so. Not soon enough. If production maintains a 1% price drop per month and manufacturing scales up to meet demand, we can get most of the way there by 2033.

The sooner we get there, the sooner we can begin to roll back damage to the environment caused by breakneck industrialization and exploitation of fossil carbon. Any and all steps to increase the manufacturing growth rate are needed. If we can contract the production doubling time from three years to 18 months, we can reduce the backlog from 10 years to just 4. 300 GT of CO2 emission avoided, 0.6°C temperature rise averted, tens of millions of lives saved.

Substituting solar power into our electrical grid and atmospheric CO2-derived hydrocarbons into our fuel supply chain is just the beginning. We want to support a future of abundance and wealth, while avoiding starvation even as legacy climate damage shifts rainfall patterns and causes extreme weather.

Let’s take the Colorado River as an example. Historical average flows of 22,000 cubic feet per second (cfs) were mediated through several large dams, diverted for agriculture and city water supplies, and support about $1.4t of US GDP annually. A series of more recent droughts have seen the annual flow collapse to less than half the historical average. The river is drying up, and with it the communities that depend on it.

There are higher value uses for water but modern reverse osmosis (RO) desalination plants can generate a cubic meter of fresh water from the ocean for just 2.5 kWh. This works out to 250 kW per cfs, or 5.5 GW for the entire Colorado River. That is, the entire flow could be replaced by RO for just one 5.5 GW power plant adjacent to enough RO to exceed total Saudi desal capacity by a factor of 10. If it were solar powered, we’d need more like 15 GW of capacity to operate just during the day, and about 3x this again to pump the water up over the intervening mountain ranges towards the Colorado headwaters.

This sounds like a continent-traversing water transport megaproject, but we’ve done it before. Back before RO and solar power, water scarcity in California was solved on a generational time scale by the visionary construction of an enormous network of canals and pumps that effectively terraformed large swaths of the state, and which we take for granted now. But for climate change, this system would be adequate indefinitely but the times have found us, yet again.

Artificially supporting the Colorado river’s flows in their entirety would cost only a few billion dollars a year – not even cents on the dollar compared to its economic productivity. It is true that the Colorado is not a large river by global standards, but if we’re facing global water shortages we should be happy to have effectively infinite extremely cheap solar power available to re-irrigate what limited arable land we must depend on. 300 TW of solar PV build out for synthetic fuels and electrification will drive costs low enough that, should we need it, we can augment the natural water cycle and reverse desertification at arbitrary scale.

We need better, faster, cheaper ways to make PV panels. Investors and developers can count on extremely robust market demand going forward. Any economy that can support manufacture of PV or parts of the supply chain should work towards that rather than rely on imports from other countries desperate to sate their own energy demands.

The power is in our hands. No part of this transition requires alien technology, 50 years of fundamental R&D, or miracles of human coordination. We need only take existing functioning processes and mechanisms and turn them up to 11.

How can I invest my money towards this future

LikeLike

A lot of solar companies are publicly traded.

LikeLike